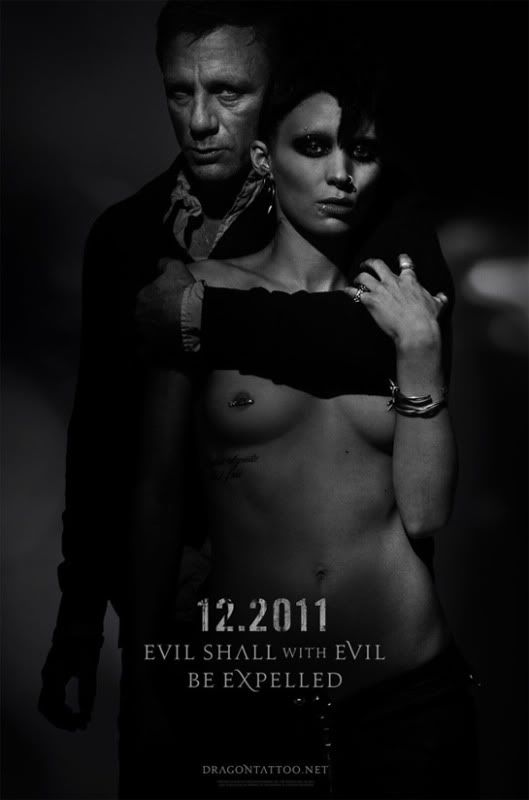

Pictured: Rooney Mara and Daniel Craig

Many people have been presenting David Fincher’s “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” under the misnomer of “remake.” Of course, the best-selling Steig Larsson series was adapted in 2009 into three Swedish-language films, but the two variations are almost incomparable beyond the fact that they are based on the same source material.

Obviously, the most stand-out point of departure that has indeed been the focus of virtually all attention paid to this film, is the performance of Rooney Mara as the iconic character Lisbeth Salander. Mara handles herself well, but at times reveals a bit too much of her own intimidation of the character. Her Lisbeth is steady and calculating but with a level of insecurity and vulnerability that Noomi Rapace for the most part lacked. Mara’s Salander was much more devoted to a sense of personal justice rather than justice for all. When she goes back for revenge on the man that violated her, it is more to make things right for herself rather than to act as crusader to the universal victim.

The black and white perception of morality that so defines the character is there, but not to the universal degree that it was with Rapace, which was, in my own opinion, the greatest strength of her interpretation of the role. Mara’s strength is her ability to connect with the emotional life of the character, honing in on the few things she genuinely does care deeply about. With a role that can so easily descend into “badass female” cliché, Mara’s frailty combats her appearance into a very complicated, if not quite as remorseless sense of the character. This is not to say one is better than the other, but each actress gave what the other lacked. Combine the two performances into one, then we would have the true Lisbeth Salander of Larsson’s novels.

In what does become a rather convoluted plotline (all those Vangers!) Fincher characteristically keeps the story fast, but evenly paced, while still presenting a surprisingly comprehensive adaptation of the novel. What changes were made were excusable and necessary to maintaining the atmosphere of Fincher’s vision of the story, which seems to be to create the effect of retreating ice as one by one the events unfold.

Daniel Craig, as disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist, the man hired to investigate the 40-year-old crime that makes up the plot, successfully de-Bond’s himself into a curious but self-conscious makeshift detective. His chemistry with Mara is spot-on as a kind of platonic if not paternal figure, but they still remain completely believable as not only business, but romantic partners. Fincher has repeatedly stated in interviews that for him, the heart of the story lies in the relationship between Blomkvist and Salander as a new breed of good-cop bad-cop, and it is clear that this was his chief conceptual focus. I would certainly not be the first to say it was extremely successful. Mara and Craig, Mara in particular, turn an extremely plot-driven thriller into an intimate portrait of two lost souls, and indeed that seems to be exactly what Fincher, and quite probably Larsson himself, had in mind.