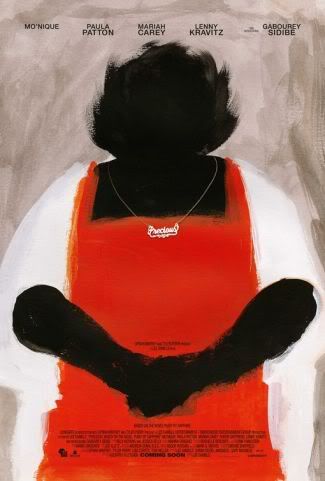

When I first saw the trailer for Lee Daniels’ film Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire, I, like many fellow moviegoers, was wary about rushing out to see it. From the images shown, it looked like a film intent on depressing its viewers beyond a point of recovery, and I had no interest in seeing a movie that was upsetting for the sake of being upsetting. However, even then a part of me did understand that whatever this movie was, it was important. And after having seen it, I can only reinforce that sentiment.

Claireece Precious Jones is obese, illiterate, impoverished, pregnant with her second child (by her father) and HIV positive. Her mother (played by Mo’Nique, in a performance I shall extol upon later) is lazy, also very overweight, and monstrously abusive. And yet, Precious courageously holds fast to her dreams of eventual superstardom and the possession of a light-skinned boyfriend (referred to in the film as ‘Tom Cruise’). She retreats into these fantasies during moments of especially horrific abuse, for example, during a particularly brutal scene of rape perpetrated by her father.

Thankfully, amidst all this unbelievable, though tragically realistic, adversity, Precious encounters individuals determined to help her realize her potential. The first of these is Ms. Rain (Paula Patton), a teacher at the alternative school Precious is asked to attend after being forced out of her public school (where she was repeating the 8th grade at the age of 16). Ms. Rain encourages Precious and her classmates to express their thoughts and emotions through writing. This proves a formidable task as most of the girls in the class are scarcely above functional illiteracy. Yet each of them, Precious included, finds any means necessary to get the words down. However, in one scene, shortly after she is diagnosed with HIV, Precious refuses to write, simply scrawling “Why me?” across the page. Unwilling to relent, Ms. Rain forces her to write, understanding that its therapeutic effects are needed now more than ever.

The other figure is Ms. Weiss, played by a surprising Mariah Carey, who effectively de-glammed herself almost beyond recognition for the role. Ms. Weiss is the social worker Precious must consult in order to obtain the welfare her mother insists she get. Despite their sometimes combative relationship, Ms. Weiss ultimately admits that she does like Precious, either as a result or in spite of the harrowing tales of abuse she has been told. Carey, whose last major screen performance was in “Glitter” – a film that audiences and I’m sure Carey herself would like to forget, is unexpectedly effective in this film. She acts as the audience’s representative within the story by having appropriate reactions of horror to many of Precious’ admissions, in particular that her Downs Syndrome daughter is called “Mongo – short for Mongoloid.”

In her debut performance, Gabourey “Gabby” Sidibe is a stunner. Like many viewers and critics, I too feared (and on some level assumed) that Sidibe was simply playing herself in the film. I was entirely wrong. After watching interviews with the young actress, Sidibe is thankfully a very joyful, articulate, and intelligent young woman. We see glimmers of this during the film through Precious’ fantasies and lighter moments as she jokes with classmates, but for the most part, she speaks in a low miserable drone, a stark contrast to Sidibe’s high-pitched bubbliness.

But the real star of this film is Mo’Nique, in what I can only refer to as one of if not the gutsiest performance I have ever seen from an actress. As a professional comedian, Mo’Nique moves to the complete opposite end of the spectrum as Precious’ atrocious, severely disturbed mother, Mary. There are moments in this film where I had to wonder what it took for Mo’Nique to bring herself to such a plane on which Mary’s psychosis resides. The answer is a tragedy in itself, as when answering this very question to Ellen DeGeneres, Mo’Nique confessed to having suffered abuse as a child from her oldest brother, Gerald. Regardless of where the performance came from, it is where it goes that it is the true triumph. In the highly emotional climactic scene, Mo’Nique sobbingly regales a thunderstruck Ms. Weiss with the history of sexual abuse afflicted upon Precious by her father. At no point are we asked to forgive Mary for allowing what has happened to Precious to happen, but I speak for many audience members when I say that when she began to weep, I wept along with her, if only out of having to face the question of what horrific events Mary must have witnessed to bring her to such a tormented place.

Precious triumphs in its ability to make a point without preaching it to us. We see Precious, we hear Precious, and we know she is real. The film does not ask us to punish ourselves for having judged people in her situation, but it does ask us to reconsider our outlook on those who, though we may not at first know it, have really never been given a chance at life. And in this way Precious bears a great responsibility as a statement to a country that has recently elected an African American president. The film is not necessarily about race relations. It is not about the fact that Precious is African American. It is about how prejudice can exist even within a racial community, and within a single individual. In one scene, Precious looks at herself in the mirror and imagines a thin, blonde, Caucasian girl staring back. As her sense of self-worth grows, she gains the confidence to look into the mirror and see her true reflection. Lee Daniels masterfully presents us with a commentary on the state of discrimination, not a lecture, and that is what makes Precious one of the most unique, jarring, and ultimately powerful films of recent history. Bravo.

No comments:

Post a Comment